Saint Therese of the Child Jesus

of the Holy Face

Entries in poetry of St. Therese of Lisieux (5)

125 years ago with St. Therese: "The Canticle of Celine," April 28, 1895

One Sunday in March 1895 Celine suffered a small disappointment that gave birth to Therese's longest poem, "The Canticle of Celine: What I Loved." Celine had entered six months before and was now a novice. Of course, she had some struggles in adapting to the minute rules of Carmelite life, which governed her smallest actions. (For examples, see the Paper of exaction on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, which gives much insight into the schedule and customs according to which Therese lived). Celine saw one of the first snowdrops in the garden of the Carmel and was about to pluck it when Therese reminded her: "You must ask for permission." Celine reports: "That I was no longer free even to pluck a tny flower was too much for me." In her cell, overcome with sadness, she wanted to write a poem to remind Jesus of everything she had sacrificed for him. Only these two lines came:

The flower that I pick, O my King,

Is You!

Over the next few weeks Therese wrote this canticle, incorporating Celine's couplet, to celebrate all that Celine had received in the past--the love of God, of her family, and of the natural world--and to insist that, in Jesus, she has them all again. She has lost nothing. Therese acknowledges that the poem is indebted to the Spiritual Canticle of St. John of the Cross. In it she recalls the same memories of her own childhood she has called to mind for the beginning of her memoir, which she is writing in these same weeks. It's a rich text to study Therese's relationship with creation. On April 28, 1895, Therese gave Celine a revised draft for Celine's 26th birthday.

Celine and Therese freely chose to become "prisoners in Carmel." In these days of the pandemic, when we ourselves are deprived of moving freely among the beauties of the world, the poem has special significance for us:

Jesus, you are the Lamb I love.

You are all I need, O supreme good!

In you I have everything, the earth and even Heaven.

The Flower that I pick, O my King,

Is You! . . .

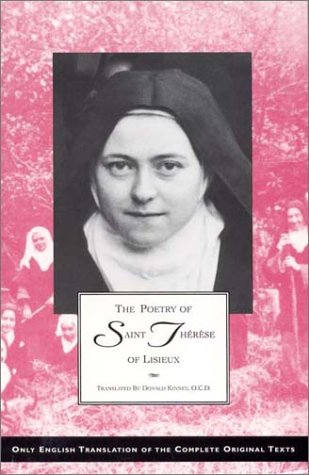

Therese attached great importance to this poem. In March 1897 she copied a few verses for Maurice Belliere, her seminarian-brother, titling the synthesis "He Who Has Jesus Has Everything." The text of Therese's poems is available online thanks to the generosity of the Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites and the Web site of the Carmel of Lisieux. To understand the poems better, I recommend consulting the valuable introductions to them in The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux, tr. Donald Kinney, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1996, pp. 93-105. Learning the context helps to integrate your understanding of each poem into your knowledge of Therese's whole life.

125 years ago with St. Therese: Celine receives the Carmelite habit on February 5, 1895

Celine Martin dressed as a bride on February 5, 1895, the day she received the Carmelite habit. Photo credit: Peter and Liane Klostermann, who photographed this portrait from an exhibit at St. Jacques Church, Lisieux. With thanks to the Carmel of Lisieux.

Celine Martin dressed as a bride on February 5, 1895, the day she received the Carmelite habit. Photo credit: Peter and Liane Klostermann, who photographed this portrait from an exhibit at St. Jacques Church, Lisieux. With thanks to the Carmel of Lisieux.

Celine Martin entered the Lisieux Carmel on September 14, 1894, six weeks after the death of her father. Her postulancy was not easy, for her health was frail; she had trouble adapting to the new diet and to the straw mattress; and her feet hurt during the long hours of standing in choir. But she emerged victorious.1 Less than five months after she entered, the Community approved her to receive the habit. The "prise d'habit" marked the end of her postulancy and the beginning of her year as a Carmelite novice. This day was considered the young woman's wedding day.

At that time the candidate left the enclosure, dressed as a bride, and participated in the Mass in the public chapel, kneeling on a prie-dieu which was cushioned and draped in white, with a tall candlestick nearby on which to place her tall candle.2 Therese had been escorted down the aisle by her father; Celine was no doubt accompanied by her uncle and guardian, Isidore Guerin, who, like her father, was a most generous benefactor to the Carmel. In Celine's memoir she writes:

. . . Ah! it was a day without clouds! . . . the snow covered the earth. I did not need like Therese to ask for it to receive it; I did not ask for flowers either and yet I got many white sprays. There was one more beautiful than any of the others, made up of flowers like lilies, it was sent to me by [Henri Maudelonde, who had asked Celine to marry him]. I was touched by this homage to my divine Spouse and I prayed a lot for the donor.

Oh! my Mother, how happy I was when I saw myself as the bride of Jesus! I could not believe my good fortune. Was it really I who, after having attended so many human marriages, finally had my turn! Yes, I was the bride, I, advancing to the altar in the white wedding dress, was alone, no mortal was by my side and my soul was singing a mysterious song to the virginal Bridegroom . . .

excerpted from the "autobiographie de Celine" on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux. Please read more of Celine's memories of that day.

Bishop Hugonin presided at the ceremony, as he had done for Therese, and dined afterward with the Guerin family.3 Father Alcide Ducellier, former vicar of St. Pierre's, preached the sermon. Therese had selected the text from the Song of Songs, 2:10-11: "The winter is past, the rains have ceased; arise, my beloved, and come." The sermon included a magnificent eulogy for Louis Martin, who had died scarcely six months ago and whose Carmelite daughters had not been present at his funeral. Therese prepared the outline for the sermon, emphasizing that, together with the gift of all his daughters, Louis offered himself to God.

. . . the memory of that venerable Patriarch, your beloved father, whom we remember on this solemn occasion. [Evoking June 15, 1888, when Celine told her father that she wanted to become a Carmelite after his death]: . . . scarcely had you spoken - in words that he could not possibly have anticipated - than he took you in his arms and pressed you to his heart. “Who am I that God should shower me with such honour!” he exclaimed. “I am truly an exceedingly happy father.” And he asked you to go with him immediately and kneel before the tabernacle.

“Come, let us go together to thank God for all the special graces he has given our family.” “God honours me by asking for all my children: I joyfully give them to him. If I possessed anything better, I would be eager to offer it to him”. Well! Even though he had nothing better to offer, and certainly nothing more dearly loved, he did have something more personal, which was himself.

Excerpted from Fr. Ducellier's letter to Mother Agnes of Jesus and Sister Genevieve after February 24, 1895, on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux. Happily, Fr. Ducellier sent the sermon to Pauline and Celine a little later, and it has come down to us verbatim. I urge you to read Fr. Ducellier's sermon in full.

Marie Guerin, who had a very sweet voice, sang a song by A. Gerbier, Il est a moi. (Three weeks later Therese would use the same melody for her extraordinary poem "To Live by Love").4 After the Mass, Celine went to the enclosure door. On the other side the community waited to receive her. As she stepped into the enclosure, she was presented with a cross, which she kissed. Then the community went before her as, on the arm of her prioress, her sister Pauline, Mother Agnes, she followed the procession into the choir. She knelt by the grille. On the other side the bishop and priests blessed the habit and asked the novice certain questions according to the manual. She answered, and, after the prayers, followed her prioress into a little room that opened out of the nuns' choir, where she was helped out of her wedding dress and into the Carmelite habit. She returned to the grille. With more prayers, the priest blessed the white mantle, the scapular, the belt, and the long veil, and Celine put them on. The priest blessed her, and the Clothing ceremony was complete.5

The Martin sisters had lost their father, and then Celine had at last joined them; only Leonie, pursuing her vocation as a Visitation nun at Caen, was missing. Celine's sister Pauline was her prioress, and we can imagine that it was a happy family day for them. The whole day was a feast in the Carmel. Trying to console Celine, who had been forced to change her religious name, Marie of the Holy Face, to Genevieve of St. Teresa, Therese had said "We will both have the same patroness now." With unconscious prescience, Celine answered: "You will be my patroness."6

Therese's gift to Celine was a poem, "Song of Gratitude of Jesus' Fiancee." The nuns usually sang at evening recreation to honor the bride of the day, and Therese wrote this poem to be sung to the melody "O saint Autel," which had been the processional hymn on her First Communion day.7 Therese's sixteenth poem, it is believed to introduce the second, "majestic" stage of her poetry.8 Undoubtedly written while Celine was still called "Marie of the Holy Face," it begins:

"You have hidden me forever in your Face!"

Speaking for herself as well as for Celine, Therese writes of

"the inexpressible grace of having suffered . . .

that by the Cross we save sinners . . .

by the Cross my ennobled soul has seen a new horizon revealed."

This "new horizon" will lead Therese to other "inexpressible graces" during this year of profound grace, 1895.

I urge you to read the poem (six stanzas of only four lines each) at the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux. Thanks to the generosity of the Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, the text of Therese's poems may be read there online. For a deeper understanding of these poems (most written in 1895, 1896, and 1897, the years we will, please God, explore for the next three years in our series "125 years ago with St. Therese"), it is indispensable to consult The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux, tr. Donald Kinney, O.C.D. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 1995). The General Introduction by Jacques Longchampt and the introductions to each poem offer invaluable context for appreciating the poems.

1. Celine, Sister and Witness of St. Therese of the Child Jesus, by Stephane-Joseph Piat, O.F.M. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997, pp. 62-63.

2. "Cérémonial à l'usage des religieuses carmélites déchaussées de l'Ordre de Notre-Dame du Mont-Carmel érigé en France selon la première règle. Nouvelle édition. Paris: Mersch, imprimeur 1888. On the Web site of the archives of the Carmel of Lisieux. Book nine, chapter five.

3. Sainte Therese de Lisieux (1873-1897), by Guy Gaucher. Paris: Editions du Cerf, 2010, p. 415, note 3.

4. Gaucher, pp. 415-416.

5. "Cérémonial," book nine, chapter five.

6. Piat, p. 63

7. The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux, tr. Donald Kinney, O.C.D. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 1995), p. 85.

8. Poetry, Kinney, p. 15.

125 years ago with St.Therese: "Song of Gratitude to Our Lady of Mount Carmel," July 16, 1894

July 16, 1894 was the 26th birthday of Sister Martha of Jesus, a lay-sister who entered three months before Therese. This birthday furnished the occasion for Therese's seventh poem, "Song of Gratitude to Our Lady of Mount Carmel." The poem takes its inspiration from the circumstances of Sister Martha's life.

July 16, 1894 was the 26th birthday of Sister Martha of Jesus, a lay-sister who entered three months before Therese. This birthday furnished the occasion for Therese's seventh poem, "Song of Gratitude to Our Lady of Mount Carmel." The poem takes its inspiration from the circumstances of Sister Martha's life.

One of the best ways to understand Therese's way is to get to know the women with whom she lived in Carmel. Learn more about the young woman who lived close to Therese for nine years:

125 years ago with St. Therese: "Saint Cecilia," Therese's first long poem, written for Celine's 25th birthday on April 28, 1894

Icon of St. Cecilia, patron of music, by Brother Mickey McGrath, OSFS. Available from Trinity Stores; for information, click on the icon.

For Celine's 25th birthday, April 28, 1894, Therese wrote her third poem, and her first long one. Although it is now titled "Saint Cecilia," (ACL),* the copy she sent to her sister bore the title "The Melody of Saint Cecilia."

Who was St. Cecilia for Therese?

Cecilia was an early Roman martyr. Although many of the stories about her life are legend, her existence and martyrdom are historical facts. Therese tells us in Story of a Soul that her devotion to Cecilia dates from her pilgrimage to Rome in November 1887. When she visited Cecilia's tomb and the site of her house, transformed into a church at her request and learned that Cecilia was named patron of music

"in memory of the virginal song she sang to her heavenly Spouse hidden in the depths of her heart, I felt more than devotion for her; it was the real tenderness of a friend. She became my saint of predilection, my intimate confidante. Everything in her thrilled me, especially her abandonment, her limitless confidence . . .

Story of a Soul: The Autobiography of St. Therese of Lisieux, tr. John Clarke, O.C.D. Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 3rd ed., 1996.

Read Therese's full account of her visit to the tomb and church of St. Cecilia on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux.

Cecilia, a consecrated virgin, was to be married against her will to the pagan Valerian, and, while the instruments sounded to celebrate her nuptials, she went on singing to the Lord in her heart, as the Office for her feast says. This abandonment captured the imagination of the 14-year-old Therese instantly.

Why did Therese write about Saint Cecilia for Celine?

Celine was the Martin sister who stayed longest in "the world." She had managed a household, cared (with the aid of Leonie till 1893) for her sick father, and refused two proposals of marriage. While participating in the active social life of the Guerin family, she had made a private vow of chastity. She would stay with Louis until his death. As the Lisieux Carmel was not likely to accept a fourth nun from the same family, what she would do then was unclear. Faced with the dilemma of Celine's future, Therese explored Cecilia's spiritualitym more deeply. She had proposed the abandonment of Cecilia as a model to her sister in her extraordinarily rich letter of October 1893 for Celine's feast: "the dear little St. Cecilia, what a model for the little lyre of Jesus . . ." (ACL)

Letters of Saint Therese of Lisieux, Vol. II, tr. John Clarke, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 1988, pp. 826-829. Read Therese's full letter on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux.

Now, having written only two poems, she produces a "symphony" for her sister in "Saint Cecilia" (ACL). The poem's themes, dear to Therese, show the connection between virginity, marriage, and martyrdom. Above all, the poem celebrates Cecilia's abandonment in lines that foreshadow the way of confidence and love Therese will discover soon after Celine enters in September:

You sang this sublime canticle to the Lord:

"Keep my heart pure, Jesus, my tender Spouse!.."

"Ineffable abandonment! Divine melody!

You disclose your love through your celestial song.

Love that fears not, that falls asleep and forgets itself

On the Heart of God, like a little child...

Your chaste union will give birth to soulsWho will seek no other spouse but Jesus.

What happened to the poem later?

During the next three years, Therese shortened and rewrote this poem, sending copies to her spiritual brothers, Adolphe Roulland and Maurice Belliere. Her extensive editorial work shows how important she thought this early poem was. In 1897, she produced a "second edition" with the intention of its being distributed after her death, and this edition is the one ultimately published. Thanks to the generosity of the Washington Province of Discalced Carmelite Friars, you can read the poem online on the incomparable Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux. (In this article, the citation ACL indicates that the source is the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux).

For a fuller understanding of Therese's poetry, I recommend the book The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux, tr. Donald Kinney, O,C.D. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelite Friars, 1996). To grasp the context and the full richness of Therese's poetry, the introductions and notes to each poem in this book, which are not available online, are invaluable.

[Purchasing through the links in this article supports this Web site].

St. Therese of Lisieux and the Sacred Heart of Jesus

Therese wrote this poem in 1895, either in June or in October, at the request of her sister, Marie of the Sacred Heart. She does not understand the Heart of Jesus as demanding reparation, but as "burning with tenderness." Jesus is the "only Friend whom I love," "my happiness, my only hope." Unable to see his bright face or hear his voice, she still can rest on the Sacred Heart. In her daring climax, she chooses that Heart for her purgatory.

“To the Sacred Heart of Jesus”

. . . .

To be able to gaze on your glory,

I know we have to pass through fire.

So I, for my purgatory,

Choose your burning love, O heart of my God!

On leaving this life, my exiled soul

Would like to make an act of pure love,

And then, flying away to Heaven, its Homeland,

Enter straightaway into your Heart.

The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux, tr. Donald Kinney, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 1996, pp. 117-120. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

To read this and all Therese's 54 poems, please order a copy of the book "The Poetry of Saint Therese" by clicking on the icon below. This book is the only English translation from the critical and complete edition of Therese's manuscripts of her poetry. Even if you have read some other translation, I urge you to read this one, which includes the original French text and an English introduction and notes rich in interest.

[Purchases through this link support this Web site].

You may also read the text (but not the introduction and notes) of "To the Sacred Heart of Jesus" online thanks to the generosity of the Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites and the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux.