Saint Therese of the Child Jesus

of the Holy Face

Entries in Marie Guerin (6)

125 years ago with St. Therese: her cousin Marie Guerin enters Carmel. For her Therese writes "Canticle of a Soul Having Found the Place of its Rest," Poem 21

St. Teresa of Avila praying before an image of Christ captive. (Licensed from Shutterstock Images)

St. Teresa of Avila praying before an image of Christ captive. (Licensed from Shutterstock Images)

On August 15, 1895, the feast of the Assumption (which was her personal feast-day), Therese's cousin Marie Guerin entered the Carmel of Lisieux. Marie, at 25 a little less than three years older than Therese, was the younger daughter of Isidore Guerin, the brother of Therese's mother, St. Zelie, and his wife, Celine. Marie was lively, witty, affectionate, sensitive, and gifted with a beautiful soprano voice.

The feast of the Assumption

Even before her entrance, Marie had kept the feast of the Assumption as her personal feast-day (what is now sometimes called a "name day"). Before Celine's entrance in 1894, Marie had posed for Celine, who took a photograph of Marie to serve as a model for a painting of the Assumption Celine painted for the chapel of the Benedictines at Bayeux. (if you click on the link to the photograph on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, you will find a link to Celine's resulting painting).

Madame Guerin had written Pauline, who was then prioress, asking deferentially that Marie's entrance might be set for her feast, August 15. Marie's mother and father, both fervent Catholics, found her vocation a privilege, but they were deeply saddened by losing her. Their older daughter, Jeanne, had married five years before and moved to Caen with her husband, and Marie's entrance left them bereft.

Therese as assistant novice mistress

From the time of Pauline's election as prioress in 1893, she confided privately to Therese the formation of the novices (Martha of Jesus, Marie-Madeleine of the Blessed Sacrament, Marie of the Trinity, Genevieve of St. Therese (her sister Celine), and now Marie Guerin, who took the name Marie of the Eucharist). Mother Gonzague held the title of novice mistress; Therese was dubbed "senior novice" and assigned merely to help her, but Pauline said later that she was, in fact, depending on Therese to form all the novices. Marie Guerin, the last to enter during Therese's lifetime, brought the number of novices to five: an injection of youth and energy to the community.

Therese's poem "Canticle of a Soul Having Found the Place of Its Rest"

It was the custom for the new postulant to sing something for the community at evening recreation on the day of her entrance. To showcase her cousin's lovely voice, Therese composed the poem "Canticle of a Soul Having Found the Place of Its Rest." As usual, she wrote with sensitivity to the person and the occasion, but also expressed her own desires:

O Jesus! on this day. you have fulfilled all my desires.

From now on, near the Eucharist, I shall be able

To sacrifice myself in silence, to wait for Heaven in peace.

Keeping myself open to the rays of the divine Host,

In this furnace of love, I shall be consumed,

And like a seraphim, Lord, I shall love you.*

Sister Therese of St. Augustine left us testimony about what Therese meant by "loving like a seraph" in the "furnace of love." At the 1910 Process, she testified:

In Sister Therese, the love of God dominated everything else; her dream was to die of love. But then she would add: "To die of love, we must live by love." So she strove to develop this love day by day, because she wanted it to be of the highest quality. Her ambition was to love like a seraph, to be consumed by the devouring flames of pure love without feeling them, so that her self-sacrifice would be as complete as possible.**

"Living on Love!," Therese's poem from February 1895

In this "Canticle," Therese sets forth some elements of a programme of life for her cousin. But on the same day she left on Marie's bed in her new cell, the manuscript surrounded by flowers. a copy of her earlier poem "Living on Love!," written during the Forty Hours Devotion in February 1895. This composition sets forth a far more powerful and detailed spiritual itinerary, rooted in the gospels and unlimited in scope. Celine called it "the king" of Therese's poems. The editors write of "the solemn fervor of this love poem," and its 15 stanzas are inexhaustible. Here I quote only stanza five:

Living on Love is giving without limit

Without claiming any wages here below.

Ah! I give without counting, truly sure

That when one loves, one does not keep count!...

Overflowing with tenderness, I have given everything,

To His Divine Heart..... lightly I run.

I have nothing left but my only wealth:

Living on Love.***

1895: a year of grace for Therese

Marie's entrance enhanced the richness of the year 1895, the year of "the Mercies of the Lord" for Therese. In 1894 she had been delivered from her father's long trial and now felt his closeness. Then her deep desire of having Celine, her inseparable companion, join her in Carmel had been fulfilled. After her rich play "Joan of Arc Accomplishing Her Mission," she had, at the request of Pauline, her prioress, begun to review her life and write her "thoughts on the graces God has granted" to her. This review brought the graces of the past vividly before her. In February Celine received the Habit, and her father's virtues were evoked in the sermon on that occasion. Later in February Therese was inspired to write her great poem "Living on Love." On June 9 she received the great grace of being inspired to offer herself, with Celine, to the Merciful Love of God. During the summer she persuaded her oldest sister, Marie, to offer herself as well. Now her cousin was coming to fulfill her vocation.

In the community context, the Martin sisters were rather prominent at this time. The community had elected Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus, prioress in 1893, at the early age of 31. This was a great grace for Therese. Their oldest sister, Marie of the Sacred Heart, was "provisoire" (in charge of procuring food for the community). Therese was charged with helping to form the novices, and her poems and religious plays were beginning to make her a little more known among some of the nuns. Only a few suspected the fire of love burning in her heart.

_________________________

* "The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux," tr. Donald Kinney, O.C.D. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 1996), p. 112.

** "St. Therese of Lisieux by Those Who Knew Her," ed. and tr. Christopher O'Mahony, O.C.D. (Dublin: Veritas Press, 1973, p. 193.

*** The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux, op. cit., p. 90.

An essay illustrated with 19th century photos to celebrate the annniversary of the day St. Therese of Lisieux entered Carmel, April 9, 1888

Therese Martin entered Carmel on Monday, April 9, 1888. That year April 9 was the feast of the Annunciation, which had been transferred from March 25 because of Lent. This photo essay is to celebrate the anniversary of her entrance.

Therese a few days before she entered on April 9, 1888

Let's listen to some accounts of her entrance. First, Saint Therese's own:

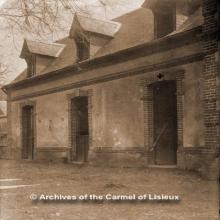

"On the morning of the great day, casting a last look upon Les Buissonnets, that beautiful cradle of my childhood which I was never to see again, I left on my dear King's arm to climb Mount Carmel.  Chapel entrance of Lisieux Carmel photographed shortly after Therese's death

Chapel entrance of Lisieux Carmel photographed shortly after Therese's death

As on the evening before, the whole family was reunited to hear Holy Mass and receive Communion. As soon as Jesus descended into the hearts of my relatives, I heard nothing but sobs around me.

The sanctuary of the chapel of the Lisieux Carmel in the time of St. Therese

The sanctuary of the chapel of the Lisieux Carmel in the time of St. Therese

I was the only one who didn't shed any tears, but my heart was beating so violently it seemed impossible to walk when they signaled for me to come to the enclosure door. I advanced, however, asking myself whether I was going to die because of the beating of my heart! Ah! what a moment that was. One would have to experience it to know what it is.

Louis Martin, probably at age 58, about 1881

Louis Martin, probably at age 58, about 1881

My emotion was not noticed exteriorly. After embracing all the members of the family, I knelt down before my matchless Father for his blessing, and to give it to me he placed himself upon his knees and blessed me, tears flowing down his cheeks. It was a spectacle to make the angels smile, this spectacle of an old man presenting his child, still in the springtime of life, to the Lord!

Space where Louis knelt to bless Therese when she entered, April 9, 1888A few moments later, the doors of the holy ark closed upon me, and there I was received by the dear Sisters who embraced me. Ah! they had acted as mothers to me in my childhood, and I was going to take them as models for my actions from now on. My desires were at last accomplished, and my soul experienced a peace so sweet, so deep, it would be impossible to express it."

Space where Louis knelt to bless Therese when she entered, April 9, 1888A few moments later, the doors of the holy ark closed upon me, and there I was received by the dear Sisters who embraced me. Ah! they had acted as mothers to me in my childhood, and I was going to take them as models for my actions from now on. My desires were at last accomplished, and my soul experienced a peace so sweet, so deep, it would be impossible to express it."

(Story of a Soul: The Autobiography of St. Therese of LIsieux, tr. John Clarke, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 3rd ed., 1996. Used with permission).

Canon Delatroette

Canon Delatroette

St. Therese writes "A few moments later." She tactfully omits what other witnesses report happened in those few moments. Canon Jean-Baptiste Delatroette, the parish priest of St. Jacques, was the ecclesiastical superior of the Lisieux Carmel (the priest charged with supervising, from the outside, this community of women religious). He had bitterly opposed Therese's entrance, believing her too young, but was overruled by his bishop, who left the decision up to the prioress. Before Therese crossed the threshold, and in the presence of her father and her sisters, Canon Delatroette announced "Well, my Reverend Mothers, you can sing a Te Deum. As the delegate of Monseigneur the bishop, I present to you this child of fifteen whose entrance you so much desired. I trust that she will not disappoint your hopes, but I remind you that, if she does, the responsibility is yours, and yours alone." He could not have foreseen that twenty-two years later Pope St. Pius X would call this girl "the greatest saint of modern times."

Much less well known than Saint Therese's account of her entrance is Celine's description of her experience of the same moment. Celine and Leonie were present with their father at the short ceremony.

Celine and Leonie the year after Therese enteredAfter writing of how inseparable she and Therese had been, Celine continued:

Celine and Leonie the year after Therese enteredAfter writing of how inseparable she and Therese had been, Celine continued:

It took much yet to get to Monday, April 9, 1888, where the little Queen left her own, after we heard Mass together in the Carmel, to join her two older sisters in the cloister. When I gave her a farewell kiss at the door of the monastery, I was faltering and had to support myself against the wall, and yet I did not cry, I wanted to give her to Jesus with all my heart, and He in turn clothed me in his strength. Ah! how much I needed this divine strength! At the moment when Thérèse entered the holy ark, the cloister door which shut between us was the faithful picture of what really happened, as a wall had arisen between our two lives." (from the obituary circular of Celine Martin, Sister Genevieve of the Holy Face, copyright Lisieux Carmel; translation copyright Maureen O'Riordan 2013).

The enclosure door which shut between Celine and Therese on April 9, 1888Saint Therese continues, writing of her impressions that first day: "Everything thrilled me; I felt as though I was transported into a desert; our little cell, above all, filled me with joy." St. Therese occupied three cells in Carmel, and until now few people have seen even a photograph of that first cell, for the photo commonly published was of Therese's last cell. Thanks to the generosity of the Archives of the Lisieux Carmel, we can at last see early photos of the room Therese saw that day. It was on the corridor near the garden:

The enclosure door which shut between Celine and Therese on April 9, 1888Saint Therese continues, writing of her impressions that first day: "Everything thrilled me; I felt as though I was transported into a desert; our little cell, above all, filled me with joy." St. Therese occupied three cells in Carmel, and until now few people have seen even a photograph of that first cell, for the photo commonly published was of Therese's last cell. Thanks to the generosity of the Archives of the Lisieux Carmel, we can at last see early photos of the room Therese saw that day. It was on the corridor near the garden:

The corridor with the door to Therese's first cell standing openThis cell looked out on the roof of the "dressmaking building" where habits were made:

The corridor with the door to Therese's first cell standing openThis cell looked out on the roof of the "dressmaking building" where habits were made:

Carmelite postulants wore a secular dress with a little capelet, and a small net bonnet on the head. The photograph below of Marie Guerin as a postulant (she entered August 15, 1895) shows how St. Therese and all postulants dressed until they received the habit.

Learn more about the Carmelite life Therese began to live on April 9, 1888.

The feast of the Annunciation is usually celebrated on March 25, just nine months before the feast of Christmas. Celine wrote that Therese loved the feast on March 25 "because that's when Jesus was smallest." Therese began her Carmelite life on the feast of Mary's "Yes" to her Lord. May each of us enter every day of our own lives with Therese's fervor and joy, for every day is a doorway for each of us to intimacy with God, to wholeness, and to sainthood.

Note: the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux are being digitized and posted online in English at the Web site of the Archives of Carmel of Lisieux. All the above photos are displayed courtesy of that site. Please visit it here to see thousands of pages of photographs, documents, and information about St. Therese, her writings, her family, her environment, the nuns with whom she lived, and her influence in the world. It is a true doorway to Saint Therese!

Saint Therese of Lisieux and the Blessed Sacrament: for the feast of Corpus Christi, May 29, 2016

In 1887, St. Therese visited the crypt of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Montmartre in Paris. Later she sent her gold bracelet to be melted down to form part of this monstrance

In 1887, St. Therese visited the crypt of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Montmartre in Paris. Later she sent her gold bracelet to be melted down to form part of this monstrance

St. Therese of Lisieux shared with her whole family a passionate love for Jesus in the Eucharist.

- At age 22 Therese recalled in the language of mystical union the experience of her First Holy Communion. (Web site of the archives of the Carmel of Lisieux)

- She remembered participating in religious processions on the great feasts:

"I loved especially the processions in honor of the Blessed Sacrament. What a joy it was for me to throw flowers beneath the feet of God! Before allowing them to fall to the ground, I threw them as high as I could, and I was never so happy as when I saw my roses touch the sacred monstrance."

(Read more about Therese's childhood experience of the great feasts of the Church at the Web site if the archives of the Carmel of Lisieux).

- In 1887, before leaving on the pilgrimage to Rome, 14-year-old Therese spent a few days in Paris with her father, St. Louis Martin, and her sister Celine. Before departing from Paris, all the pilgrims were consecrated to the Sacred Heart in the crypt of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Montmartre. Later Therese sent her gold bracelet to be melted down to form part of the monstrance pictured above, which was used for the perpetual adoration of the Eucharist. How happy she must have been to think that the substance of the little bracelet that once touched her wrist was so near her Eucharistic Lord. I thank the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Montmartre for permitting "Saint Therese of Lisieux: A Gateway" to display this photograph, which was taken in 2012 when, to commemorate the 125th anniversary of Therese's visit in 1887, her reliquary was venerated at Montmartre for several days.

- Although Therese's understanding, experience, and theology of the Eucharist continued to grow and develop throughout her short life, it was already well formed when she was only sixteen. In May 1889, during her novitiate, she received a letter from her nineteen-year-old cousin, Marie Guerin (later Sister Marie of the Eucharist). In Paris to visit the great 1889 Exposition, Marie, a young girl from the provinces, was troubled by her reaction to the nude statues in the exposition, and wrote to Therese suggesting that she could not receive Communion in that condition. On May 30, 1889, the 16-year-old novice answered with the prophetic wisdom given by the Holy Spirit:

Oh, my darling, think, then, that Jesus is there in the Tabernacle expressly for you, for you alone; He is burning with the desire to enter your heart ... so don't listen to the devil, mock him, and go without any fear to receive Jesus in peace and love!. . . ,

Your heart is made to love Jesus, to love Him passionately; pray so that the beautiful years of your life may not pass by in chimerical fears.We have only the short moments of our life to love Jesus, and the devil knows this well, and so he tries to consume our life in useless works ....

Dear little sister, receive Communion often, very often. . . . That is the only remedy if you want to be healed.

(LT 92, to Marie Guerin, May 30, 1889), from The Letters of St. Therese of Lisieux, Volume I. Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelite Friars, 1982, pp. 568-569. I repeat: if you know Therese only through her Story of a Soul, great graces await you in her letters).

In 1910 Msgr. de Teil, the vice-postulator for Therese's cause, showed this letter to Pope St. Pius X, the Pope who gave us frequent communion, and said to him "This little sister has made a commentary in advance on Your Holiness' decree on frequent communion." "Est opportunissimum! Est magnum gaudium por me!" ["This is most opportune! This is a great joy to me"], cried the Pope. He ended "We must hurry this cause." Ibid., p. 569. At the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, read the full text of Therese's letter to Marie Guerin about the Eucharist.

May our love for the Eucharist continue to grow and deepen, and may the transformation it brings us express itself not only in adoration and in frequently joining with the Christian community to celebrate the Eucharist but also in satisfying, with Jesus, all the hungers of the human family.

The anniversary of the death of Blessed Louis Martin on Sunday, July 29, 1894

Louis Martn in death. La Musse, 1894. Photo credit: Carmel of Lisieux

Louis Martn in death. La Musse, 1894. Photo credit: Carmel of Lisieux

The letter from Celine Martin, at La Musse, near Evreux, to her Carmelite sisters in Lisieux to tell them about the death of their father:

July 29, 1894

Dear little sisters,

Papa is in heaven! . . . I received his last breath, I closed his eyes. . . . His handsome face took on immediately an expression of beatitude, of such profound calm ! Tranquility was painted on his features . . . He expired so gently at fifteen minutes after eight.

My poor heart was broken at the supreme moment; a flood of tears bathed his bed. But at heart I was joyful because of his happiness, after the terrible martyrdom he endured and which we shared with him . . . .

Last night, in a sleep filled with anguish, I suddenly awakened; I saw in the firmament a kind of luminous globe . . . . And this globe went deeply into the immensity of heaven.

. . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . Today, St. Martha, the saint of Bethany, the one who obtained the resurrection of Lazarus . . . .

Today, the gospel of the five wise virgins. . . .

Today, Sunday, the Lord's day . . . .

And Papa will remain with us until August 2, feast of Our Lady of the Angels. . . .

Your little Celine

(from Letters of Saint Therese of Lisieux, Volume II. Washington, D.C.: copyright 1988 by Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, ICS Publications, pp. 874-875. Used with permission).

See also Marie Guerin's meditation, in 1895, on the first anniversary of Louis Martin's death

Below, courtesy of the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, is a photograph of the small building at La Musse in which Blessed Louis Martin died on that Sunday morning a hundred and eighteen years ago.

Excerpts from "A Map of the Way of Confidence and Love of St. Therese of Lisieux"

As a gift for the feast of St. Therese of Lisieux I publish below an excerpt from my conference "A Map of Therese's Way":

During Thérèse’s illness Céline asked her

“Do you believe I can still hope to be with you in heaven? This seems impossible to me. It’s like e, xpecting a cripple with one arm to climb to the top of a greased pole to fetch an object.”

Thérèse answered,

“Yes, but if there’s a giant who picks up the little cripple in his arms, raises him high, and gives him the object desired! This is exactly what God will do for you, but you must not be preoccupied about the matter; you must say to God, ‘I know very well that I’ll never be worthy of what I hope for, but I hold out my hand to You like a beggar, and I’m sure You will answer me fully, for You are so good!”[vi]

Thérèse’s littleness is not immaturity, but a complete detachment from self. She outlines for us a program of searching interior asceticism. She asks us to give up attachment to consolation in prayer, to beautiful thoughts, to complicated methods in the spiritual life, to all spiritual beauty-culture and all thought of ourselves as virtuous people.

“You are very little; remember that and, when one is very little, one doesn’t have beautiful thoughts.”[vii]

“For simple souls there must be no complicated ways.”[viii]

“O Mother! I am too little to have any vanity now, I am too little to compose beautiful sentences in order to have you believe that I have a lot of humility. I prefer to agree very simply that the Almighty has done great things in the soul of His divine Mother’s child, and the greatest thing is to have shown her her littleness, her impotence.”[ix]

To be little does not mean to have little hope, or little desire, or little love; it means to have no conceit, no attachment to self, but great love and great confidence in the power of God. “We can never expect too much of God, Who is at the same time merciful and almighty, and we shall receive from Him precisely as much as we confidently expect of Him.” Thérèse’s “littleness” is an experiential knowledge of the wholly gratuitous action of grace. What could be our frustration becomes our cause for joy. A child cannot take care of herself, cannot earn her living, so no one expects the child to do so. In the same way, if we acknowledge our littleness, God will accept full responsibility for us, but, if we try to go it alone, God may leave us to do so until we turn to God.

Thérèse said her way was related to the doctrine St. John of the Cross set forth in his The Ascent of Mount Carmel: “To come to possess all, desire the possession of nothing. To desire to be all, desire the possession of nothing.” At seventeen Thérèse wrote to her cousin, Marie Guérin:

Marie, if you are nothing, you must not forget that Jesus is All, so you must lose your little nothingness in His infinite All and think only of this uniquely lovable All. . . . You are mistaken, my darling, if you believe that your little Thérèse walks always with fervor on the road of virtue. She is weak and very weak, and every day she experiences has a new experience of this weakness, but, Marie, Jesus is pleased to teach her, as He did St. Paul, the science of rejoicing in her infirmities This is a great grace, and I beg Jesus to teach it to you, for peace and quiet of heart are to be found there only. When we see ourselves as so miserable, then we no longer wish to consider ourselves, and we look only on the unique Beloved! . . .

Dear little Marie, as for myself, I know no other means of reaching perfection but (love).[xii]

The teenaged Thérèse turned away from the classical ideal of sanctity: that a saint must be perfect, a brave, vigorous person who “walks always with fervor on the road of virtue.” The ideal of sanctity set before her at Lisieux Carmel included physical mortification, anxious attention to one’s state of soul, and collecting “good deeds” to enrich one’s reward in heaven. Thérèse said firmly that these methods were not for her or for “little souls.” And the life Thérèse led was not what most of the people around her expected of a saint. Sister Anne of the Sacred Heart, a nun from Saigon who lived with Thérèse for seven years before returning to Vietnam, was often asked about Thérèse after she became famous. She invariably answered: “There is nothing to say about her, she was very good and very self-effacing, one would not notice her, never would I have suspected her sanctity.”[xiii]

Most of the nuns who lived with Thérèse did not venerate her during her lifetime. She was misunderstood and rejected just as we are. Pauline said that Thérèse “often had to suffer from people’s dislike of her, from clashes of temperament or of mood, and, indeed, from spite and jealousy on the part of certain sisters . . .”[xiv]

Sister Marie-Madeleine, the novice who used to run away and hide when it was time for her to see Thérèse for spiritual direction, testified:

“She was unknown and even misunderstood in the convent. About half the sisters said she was a good little nun, a gentle person, but that she had never had to suffer and that her life had been rather insignificant. The others . . . had a more unfavorable view of her . . . they said she had been spoiled by her sisters.”[xv]

Sister Vincent de Paul once said:

“I cannot understand why they talk about Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus as if she were a saint. She does nothing extraordinary; we do not see her practicing virtue; it cannot even be said that she is a really good nun.”[xvi]

“She does nothing extraordinary. We do not see her practicing virtue.” This testimony speaks volumes about the way of confidence and love. In place of extraordinary deeds, Thérèse proposes a way of deep interior detachment, a childlike and spousal intimacy with God, and a life of hidden love.

“I am not always faithful, but I never get discouraged.”

Like us, Thérèse was not perfect. Unlike many of us, she never lost confidence that in the end she would be consumed by the fire of love:

After seven years in the religious life, I still am weak and imperfect. I always feel, however, the same bold confidence of becoming a great saint because I don’t count on my merits since I have none, but I trust in Him who is Virtue and Holiness. God alone, content with my weak efforts, will raise me to Himself and make me a saint, clothing me in His infinite merits.[xvii]

Some have interpreted Thérèse’s way to mean simply offering every little thing to God, a kind of constant “morning offering.” But a focus on Therese's little acts distorts the way, as if, instead of concentrating on doing great things for God, we should worry about doing little things for God. Thérèse does not allow us to become preoccupied with trivialities; she challenges us to let nothing escape us, to realize that the smallest happenings of our lives are all fuel for the fire of love which will transform us. She turned away from focusing on any deeds of her own, big or small, and concentrated on trusting in the action of Jesus.

“Let us not refuse Him the least sacrifice. Everything is so big in religion . . . to pick up a pin can convert a soul. What a mystery! . . . Ah! It is Jesus alone who can give such a value to our actions; let us love Him with all our strength. . . .[xviii]

In the texts Thérèse wrote we find a radical doctrine with cosmic reverberations. The “way of confidence and love” is not something we do. The heart of the little way is to revision our relationship with God, to touch the heart of God, and, above all, to let the heart of God touch our own hearts

To Thérèse sanctity is not perfection; it is bearing with one’s imperfections.

“If you want to bear in peace the trial of not pleasing yourself, you will give me a sweet home. . . . do not fear, the poorer you are the more Jesus will love you.”[xix]

“How happy I am to see myself always imperfect and to have such need of God’s mercy at the moment of my death!”[xx]

To Thérèse the holy person is not the perfect one, the superhero who has conquered weakness and limitation. To Thérèse, holiness is not a victory, but a surrender. It’s a loving acceptance of our own fragility, our weakness, our impotence, our inability to do any good on our own. And this loving acceptance is an invitation to the creative action of love and mercy in our hearts.

copyright 1988-2010 by Maureen O'Riordan. All rights reserved.

[vi] Last Conversations of St. Therese of Lisieux, tr. John Clarke, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 1977, , p. 221.

[vii] Ibid. , p. 218.

[viii] Story of a Soul (Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 1976), p. 254.

[ix] Ibid., p. 210.

[xii] Letters of Saint Thérèse, Volume I. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 1982, p. 641.

[xiii] Letters of Saint Thérèse, Volume II. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 1988, p. 1091.

[xiv] St. Thérèse of Lisieux by those who knew her.

[xv] St. Thérèse of Lisieux by those who knew her, p. 264.

[xvi] Last Conversations

[xvii] Story of a Soul, p. 72.

[xviii] Letters, Volume II, May 22, 1894, p. 855.

[xix] Letters, Volume II, December 24, 1896, p. 1038.

[xx] Last Conversations, July 15, 1897, p. 98.